TULCA 2023: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, multiple venues, Galway, 3–19 November 2023

A mysterious artist hovers around the programme for honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise. J.J. Beegan created a number of artworks during his stay at Netherne, a psychiatric hospital in East Surrey, sometime between the 1920s and ’40s. Beguiling and intimate works on paper, the artist’s drawings mostly depict animals, and many are signed ‘J.J. BEEGAN / SCULPTURER [sic] / DUNLORST / BALLINASLOE’. We don’t know much about Beegan – how he perceived his art practice, why he ended up in the asylum, whether he ever made it out. The drawings may have been preparatory drawings for sculptures, but there’s no way of knowing for sure. We also can’t be sure about the nature of his connection with Ballinasloe, a Co. Galway town that in local dialect is synonymous with St Brigid’s Hospital, the mental health institution it was home to for 180 years (‘to go to Ballinasloe’, in local idiom, means to have a mental health crisis). Beegan may have been from the town – perhaps a member of the Beegan family of stonecutters that can be recorded as living on Dunlo Street – or he may have had a stay at St Brigid’s. Who can say? With Netherne’s archives now destroyed or sealed, Beegan’s surviving artworks are the only material evidence of his existence.

Installation view of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise at TULCA Gallery, Galway, 2023. Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Beegan’s artworks, now part of London’s Wellcome Collection, are not on show (physically, at least) within honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, the 2023 edition of TULCA curated by Iarlaith Ní Fheorais. Inscribed on toilet paper with matchsticks, the drawings are just too fragile to travel. And yet they subtly permeate the exhibition programme: scanned drawings of strange animals slink onto festival branding, adorning programmes and window graphics; Beegan’s life and work are attentively discussed in the accompanying publication, taking on a symbolic and phantasmal role in the exhibition and posing questions about art-making, incarceration, archives, and (dis)ability. Who is afforded the voice to tell their own story, and who is recalled only in the medical and/or criminal reports of their custodians? Which artworks and archival materials warrant preservation and which are destroyed? Which artworks have cultural value and which are solely ‘therapeutic’, or simply ‘graffiti’, the daubings of the insane? Across six main venues, a publication and events programme, honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise teases out these questions and more.

The core venue is the TULCA Gallery on St Augustine Street – a cavernous former dole office, stripped to its concrete shell – and the first work we encounter upon entry is by Irish artist Bridget O’Gorman, who lives with a permanent spinal injury known as Cauda Equina Syndrome. Slings, hoists, and other apparatus of disability are suspended from the ceiling by elegant rods, straps, and hooks. This array of assistive devices is cast in unreinforced Jesmonite, a fragile resinous material with a chalky-seeming texture. Pinched into tubes, their floating, delicate forms show wrinkles, sags, and strain where they bend. I cannot help but think of them as limb-like, bodily: one two-pronged form dangles from the ceiling like a pair of legs, while a lipstick-red arch becomes a comic frown, a line drawing in space. Inspecting the latter closely, I notice a bulbous growth on its surface. Presumably the result of a split casting bag, it resembles a wart or abscess. A glass bubble protrudes from underneath another form, and the limp shreds of glue-on mosaics are draped under and over various tubes and poles. Conjuring prosthetic masks or skin-like forms, they bring to my mind the figure of Bartholomew in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, his flayed skin drooping down from a cloud.

Installation view of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise at TULCA Gallery, Galway, 2023, showing Bridget O’Gorman, Support | Work, 2023. Installation, dimensions variable. Photo: Ros Kavanagh

O’Gorman is primarily a sculptor but hasn’t been able to produce work of this kind for several years due to the changing conditions of her disability. The creation of this work was supported by Ní Fheorais, who is also the artist’s producer, and by Arts and Disability Ireland, who funded access to a support worker. Accessibility, then, forms both the content and the process of the works, and Ní Fheorais’s programme at large. O’Gorman’s works are a celebration of support structures, making visible the contraptions she uses to operate on a daily basis, but also an expression of fragility. Each sculpture is precariously suspended; worm-like tubes that seem like they could easily snap, or crumble into powder. Theatrically spotlit during TULCA’s evening launch event, they cast strange shadows on the floor and walls, and carry the charged energy of animate objects, waiting to spring into life.

Also suspended from the ceiling are four textile works by German artist Philipp Gufler. From an ongoing series of fifty-two ‘quilts’ and counting, each of these works commemorates a queer figure – in this case, the late nineteenth-century judge and psychiatric memoirist Daniel Paul Schreber, Weimar-era sexologist Charlotte Wolff, 1980s artist Lorenza Böttner (a trans woman who had both arms amputated after climbing a pylon as a child), and the genderqueer star of Germany’s 2003 Pop Idol, Lana Kaiser. Rather than traditional portraiture, Gufler has invoked each of these figures through materiality, colour, form, texture, and patterning, telling their stories through visual and haptic means. Schreber’s Quilt, for instance, bears hallucinogenic patterns which undulate in and out of focus as they’re orbited, referring to the schizophrenic visions (including the strong feeling that he had transformed into a woman) recounted in his 1903 Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, snippets of which trail snail-like around the fabric. Böttner’s Quilt is screen-printed three times with a modified photograph in which the artist appears playful and spectre-like, sheathed in gauzy fabric. Wolff’s features photographs of the subject from both a police document and by her friend Man Ray, presented in combination with a hand motif, a reference to her vocation as a palm reader while in exile from Nazi Germany. Finally, Gufler’s Quilt for Lana Kaiser has a clear personal resonance, collaged with photographs from the artist’s personal archive, many of which document occasions where he met the singer.

Philipp Gufler, Quilt #31 (Lorenza Böttner), 2021 Silk screen print on fabric, zipper, 95 x 180 cm. Courtesy BQ, Berlin, and the artist. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooji, Amsterdam

Offering creative and unconventional portrayals of their subjects, Gufler’s Quilts materialise the artist’s research into queer histories and figures: the artist is also a member of a queer archive in Munich, a pursuit that has clearly infused his art practice with fascinating content and visual sources. Each bearing roughly the same dimensions, the Quilts act like index cards of queer history, the four biographies chosen for TULCA spanning a period of almost 150 years. Individually, each story elucidated is fascinating. Collectively, they demonstrate the importance of remembering, of storytelling, and of looking to forebears and tracing a lineage. They point to the crucial power of the archive as a tool for bearing witness and preserving these stories. In an era in which right-wing media typifies transness as a contemporary (and invented) phenomenon, relaying the stories of figures like Schreber, Wolff, Böttner, and Kaiser give vital evidence of the existence (and struggles) of queer and gender non-conforming people throughout history. In an artist’s talk as part of the TULCA programme, Gufler pointed out that often, the only archival evidence of queer experience in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries comes in the form of medical or criminal reports (including the mugshot that appears on Wolff’s Quilt). The queer subject is rarely given a voice or permitted to tell their own story. Creating an archive through art-making that is brimming with wit, verve, and aesthetic power, then, offers a compelling counterpart to often punitive institutional reports.

Though titled Quilts, the dimensions of these works are somewhat smaller than the term might imply, and their materials are not very quilt-like (gauze and PVC both feature in this small selection). Use of this terminology is suggestive, however, of the long tradition of queer storytelling through quilt-making, most notably by various international strands of the NAMES Project, which memorialised the victims of the HIV/AIDS crisis. (Initiated in the US, the project spread to many locales including Ireland. The Irish NAMES Project’s quilts were also, coincidentally, exhibited last year at VISUAL Carlow.) Jamila Prowse, whose Crip Quilt (2023) is situated near that of Gufler in the TULCA Gallery, also continues this powerful legacy of storytelling through quilt-making. Prowse has embroidered colourful patches onto the surface of a weighted blanket, each one offering stitched musings or diaristic snapshots of day-to-day life, some from the artist’s own recollections, others drawn from oral histories by artists with disabilities. On a nearby wall, a series of monoprints by Paul Roy give darkly humorous sketches of his experience living with long-term illness (‘Drugs but not the fun kind’, reads one, ‘I can’t dance but I want to’ another). Shown side-by-side, Prowse’s and Roys’s offerings give two tonally divergent but equally frank first-person accounts of the life of an artist living with disabilities, enthused with emotion, humour, pathos, and prosaic detail.

Installation view of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise at TULCA Gallery, Galway, 2023, showing Paul Roy, (from left) I Can’t Dance, Hospital Food and Frozen, 2023. Monoprints, dimensions variable. Photo: Ros Kavanagh

The specific context of incarceration in Ireland is explored further in Galway Arts Centre. As Ní Fheorais’s essay in the publication shares, mid-twentieth-century Ireland had the world’s highest rates of incarceration per capita (astonishingly, more than Stalin’s USSR). This incarcerated population was distributed between prisons, Magdalene laundries, mother and baby homes, country homes, industrial schools, and orphanages, but the biggest proportion by far (around 0.7% of the population) was in mental health institutions such as St Brigid’s, Ballinasloe. This complex history is tackled head-on in bless every foot that walks its portals through (2023), Aisling-Ór Ní Aodha’s installation of paintings and audio works in response to the history and site of St Brigid’s. Ní Aodhna’s paintings are subdued and simplified, almost monochromatic renderings of the site and its vernacular architecture: stone-trimmed windows, heavy grey facades that shroud the interior in mystery, a solemn bell tower. A few jugs and hanging sheets can be glimpsed through the windows but not much else. Ushered into eclectic assemblages with wooden frames, the paintings are presented alongside needlework, small watercolours on paper, a painted shutter. In the accompanying audio, a gentle but rapid voice describes the material facts of the site, the specificity of its architectural detailing, finding a hushed poetry in attention to detail, and ruminating on the thorny relationship between colonialism and the Irish Free State’s policy of mass incarceration.

Installation view of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise at TULCA Gallery, Galway, 2023, showing Aisling-Ór Ní Aodha, the usual pieces of cloth (from bless every foot that walks its portals through), 2023. Audio and painting installation, dimensions variable. Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Also at Galway Art Centre, P. Staff’s seventeen-minute film Weed Killer (2017) takes a tenacious look at the politics of sickness, the body and biomedical technologies such as radiation treatments. Actress Debra Soshoux delivers a frank and impassioned monologue (adapted from Catherine Lord’s 2004 memoir The Summer of Her Baldness) detailing the abject horror of undergoing chemotherapy. Despite the bleakness of this subject matter, Soshoux’s chilling performance, coupled with striking thermogenic imagery, makes the film compelling viewing. Its harrowing account of bodily decay, focusing on the sensorial and animalistic – ‘No feasting and no fucking’ – is cut through with an emotional and impassioned lip sync performance by Jamie Crewe. Pulsating with desire and lived experience, Crewe’s blistering performance offers much-needed respite from Soshoux’s harrowing monologue, ruminating instead on the malady of lovesickness. Staff’s film demonstrates the fine line between sickness, cure, chemical treatment, and intoxication, likening chemo to ingesting weed killer. By casting trans women in the performing roles, the artist creates links between different kinds of medicalised bodies and highlights the politicised nature of healthcare.

With support from Arts and Disability Ireland, a huge effort has been made to make the TULCA programme as accessible as possible, from providing closed captioning and audio descriptions of video works to hanging wall-based works at a lower level to provide a more inclusive viewing experience. There is also plenty of seating available and moments to rest built into the architecture of the display, which feels generous to all kinds of bodies. The exhibition space at Outset, across the road from the TULCA Gallery on St Augustine Street, has even been transformed by queer collective Bog Cottage into a pleasant space to sit and reflect, socialise, and slow down. Styled as a ‘faerie fort’, a sense of play and mischief as well as relaxation is implied. Cheeky motifs of feasts and animals adorn colourful curtains made from recycled textiles, sourced in charity shops in Berlin. Fragments of poetry by Ainslie Templeton spill across the patchworked fabrics, while a mellifluous sound piece by Renn Miano impels one to linger a little longer, lolling on the custom-made seating and interacting with fellow visitors.

As well as inclusion, Bog Cottage’s work points to the importance of socialities in Ní Fheorais’s curatorial approach. This is the first TULCA since 2019 to be permitted an afterparty, so it feels pertinent that a space has been created to facilitate connection, intimacy, friendship, and community-building. These are themes that resonate throughout the programme, also coming into focus in Sean Burns’s Dorothy Towers (2022), an enchanting thirty-one-minute film about two residential tower blocks on the outskirts of Birmingham. The postwar development’s proximity to several gay nightclubs made it an unexpected haven for LGBTQ folk, particularly during the HIV/AIDS crisis. Shot on 16 mm, Burn’s film transforms the towers into shining beacons, windows shimmering in the light like synthetic gemstones. The artist celebrates the modernist architecture of the site, with its colourful tiled underpasses, overpasses, subways, and flyovers. Interviews with residents, including legendary club kid Twiggy and drag queen Seema Butt, reflect on the difficulties faced by queer residents in the ’80s and ’90s, and the importance of community bonds in the face of such hardship.

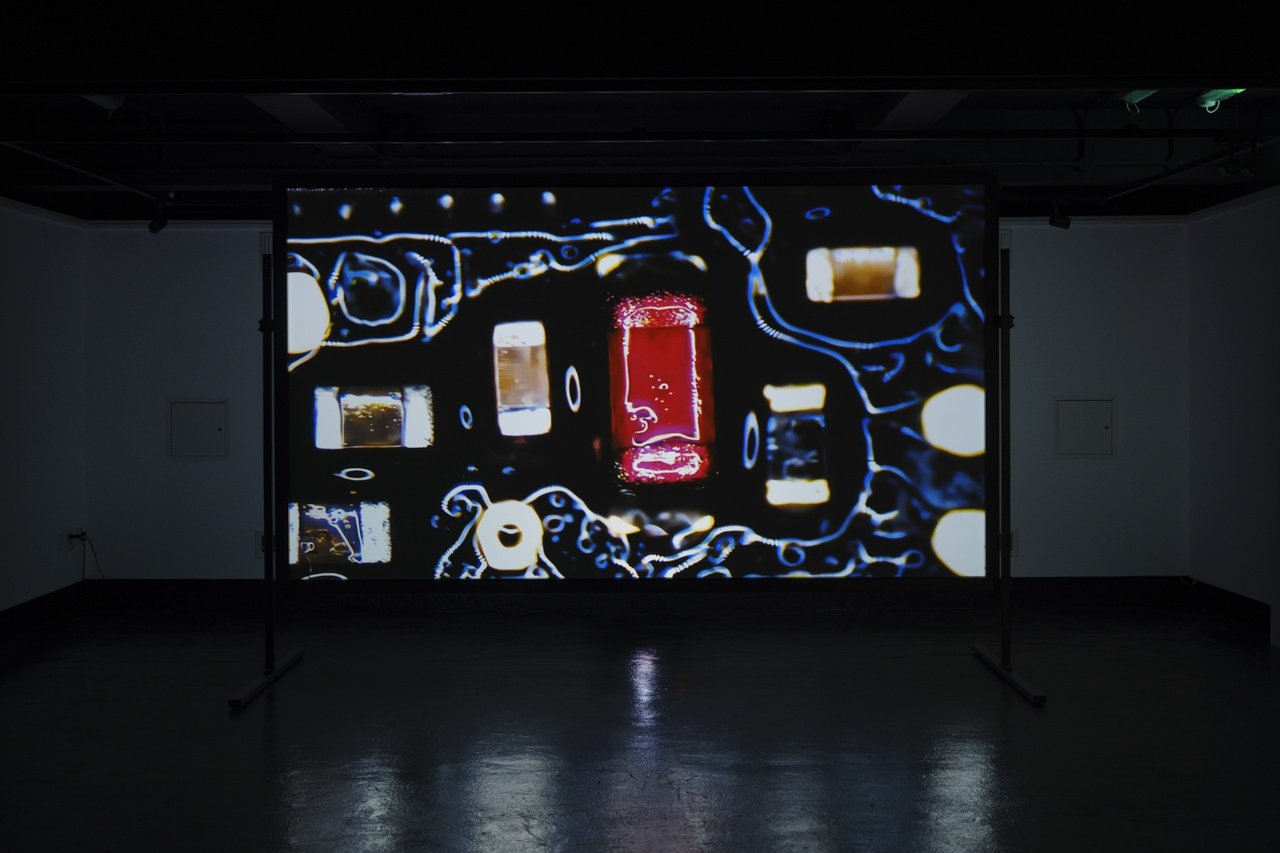

Installation view of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts: honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise at TULCA Gallery, Galway, 2023, showing Rouzbeh Shadpey, Forgetting Is The Sun, 2023. Video, duration 14 minutes 34 seconds. Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Ní Fheorais is a native Galwegian who has based herself, in recent years, in Dublin, London, and Berlin. She brings to TULCA a deep awareness and sensitive consideration of the context of the West of Ireland. Aware of the region’s complex histories in relation to mental illness, state care, and incarceration, Ní Fheorais is able to situate this within an international and intersectional context. Her programme and its accompanying publication draw parallels between the struggles faced by disabled communities and other groups that have been medicalised and ‘othered’ by a paternalistic state – most prominently LGBTQ+ and, in particular, trans people. Writing, film, sound, storytelling, and experiential works all have a strong presence in the programme, bridging the gap between archival research and more immersive, haptic, and sensory experiences. This is a valuable way to shine a light on stories that have been previously confined to archives, such as the one in which Beegan’s artworks were found.

The title of this TULCA, honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, comes from an Irish folk cure for what would have once been referred to as ‘madness’. No bold claims linking the ‘curatorial’ and the ‘curative’ are made here, but the programme does offer a generous, compassionate, and tender reflection on its sometimes challenging subject matter of sickness and incarceration, offering moments of humour, theatricality, and even a soupçon of glamour to help the medicine go down.

Rosa Abbott is a writer and curator based in London.